Nether Wallop Mill, Hampshire, England

March 24th 2014

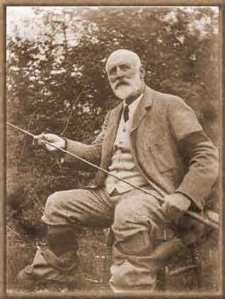

I suspect like me, you know in your heart of hearts that fly fishing is possibly the most inefficient way to catch fish as yet devised by man. If we had to capture fish to survive, the fly fishermen amongst us would be the thinnest and hungriest of the population. But we persist and indeed it’s a profession I choose to make my living. So in the year that marks the 100th anniversary of F. M. Halford’s death – the man who can be said to have invented modern-day dry-fly fishing – I sometimes feel compelled to ask, what draws us back to the river time and again when the odds are so stacked against us?

Halford was a driven man, some might say obsessive. He was a wealthy industrialist who, at the height of the Victorian era, had the time and the means to pursue his beliefs in an era when downstream wet-fly was the standard in fly fishing. Nymph fishing was as yet a twinkle in the eye of G. E. M. Skues, its invention still 25 or more years in the future. Halford set his bar very high. Not for him random or blind casting. His belief was that a true fly fisherman should first find a surface feeding fish. Then, through observation or deduction, they should identify the fly on which that fish was feeding and tie an accurate imitation of that fly to the line. Then, and only then, should the angler take up position and make a cast. Halford’s perfect day would be to spot four rising fish feeding on a different fly each time and catch all four with his first cast.

In the context of a time when fly tackle was rudimentary – silk lines, greenheart rods, cat gut leaders and spade hooks – this economy of effort makes a certain amount of sense. Goodness knows even with all our hi-tech modern kit it is easy enough to lose a fish and exasperating to re-tackle after a snagged back cast snaps off your fly, so one can only guess how long it took in Victorian times. That said, angling was a far more leisurely affair. For many of us a day on the river is a snatched treat, shoehorned into busy lives and often subject to complex family negotiations, but no such matters troubled Halford. He took a cottage on the banks of the River Test in Hampshire for the season and decamped to his beloved Oakley Stream at Mottisfont Abbey for months at a time. There he honed his dry-fly creed on a chalkstream where fish like to rise to the surface fly like no other.

I know that plenty of people will take me to task for crediting Halford for ‘inventing’ dry-fly fishing. It is true that before the birth of Christ the Macedonians were doing something similar, and angling literature from the sixteenth century onwards, including Izaak’s Walton’sThe Compleat Angler, makes reference to floating flies. There were also contemporaries of Halford’s who were pursuing the same line of thought. But what Halford did with two books published in 1886 and 1889 was codify dry-fly fishing, drawing together ancient and modern strands of thought and practice to make sense of a style of fly fishing with which most anglers were unfamiliar. Halford’s second book, Dry Fly Fishing in Theory and Practice, elevated him to super-star status in the fishing world. He became a brand before the concept of branding was really invented, with rods, reels and all manner of other angling paraphernalia carrying his endorsement. At his thatched hut on the Oakley Stream he daily welcomed visitors who came from far and wide to pay homage to a man who revolutionised the sport.

But Halford succeeded in establishing the popularity of dry-fly fishing for two reasons: when the conditions are right it can be mighty effective and it is exciting. And on the chalkstreams where he put his theories into practice it has become one of the most exhilarating ways of catching fish. There are few other places in the world where you can survey a gin-clear river that is barely knee deep and spot half a dozen fish or more holding on the current all within the distance of one easy cast. Approached with care these brown trout are not skittish – they have confidently chosen their lies so they may eye up the food that is carried down towards them at their leisure. You, like the fish, watch the progress of the insects on the water. Maybe a Hawthorn in blustery April. A huge Danica Mayfly during Duffer’s Fortnight. A pretty Blue-winged Olive on a tranquil summer’s evening or a clumsy Sedge in September. Whatever the month chalkstream trout are choosy because they can afford to be. There is more food in these rivers than you can shake a stick at and therein lies the skill of the dry-fly fisherman. Luring these trout demands a perfect imitation, presented in the correct way, at precisely the right moment.

Put that way it sounds like an impossible task but what Halford did was to open the door to the possibility of success, describing new patterns and techniques which have been gradually improved in the hundred years since his death. Man-made materials for tying, precision hooks, factory tapered leaders and even Polaroid sunglasses are just some of the many advantages we have over the anglers of his day, but the same basic principles apply. Locate. Identify. Cast. And when it all comes together there is that sublime moment when you know you have made all the right choices. The fly lands on the water, drifts towards the fish and in that split second between the fish seeing the fly and rising to the surface to take it you may revel in both anticipation and success.

So the next time you tie on a dry fly offer up a small moment to thank Frederick Halford; we owe him a mighty debt.

This article is in the current edition of the Irish Country Sports and Country Lifewww.countrysportasandcountrylife.com